An Interview with Larry G. Corey

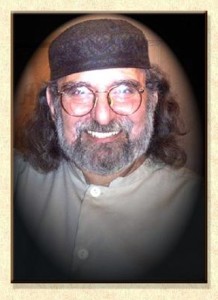

L.G. (Larry) Corey has appeared (or is scheduled to appear) in Poetry Pacific, Chaffey Review, Screech Owl, Jewcy, Evergreen Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, Midstream, Choice, The Critic, and now EmptySinkPublishing. He lives with his pit bulls and cats in a small mountain community seven thousand feet above sea level in the San Bernardo Mountains of SoCal. Larry turned 80 years old this last November, and he agreed to sit down with us for a few questions.

L.G. (Larry) Corey has appeared (or is scheduled to appear) in Poetry Pacific, Chaffey Review, Screech Owl, Jewcy, Evergreen Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, Midstream, Choice, The Critic, and now EmptySinkPublishing. He lives with his pit bulls and cats in a small mountain community seven thousand feet above sea level in the San Bernardo Mountains of SoCal. Larry turned 80 years old this last November, and he agreed to sit down with us for a few questions.

Empty Sink Publishing: Thank you for taking the time to speak with me today. Let’s start with nomenclature: can you explain your full name, Yakov Leib ben Moshe HaKohain Kalidas, for us?

Larry Corey: That actually is my given name—my Hebrew given name—when I was born. It’s the name I use when I write and publish my scholarly, religious, theological works. But the name I use—my English name—is Lawrence G. Corey: that was the name my parents also gave me. Broken down in Hebrew, my full name means Yakov (Jacob) Leib (the Heart) ben Moshe (son of Moshe) HaKohain (Rabbinical priests). My name is very traditional—remember, I was born almost 100 years ago, and my parents were just naming me the way Jewish children got named. In my own development as a poet and as a spiritual teacher, I’ve really gotten a great deal out of Hinduism. When I converted to Hinduism, I was given a name, and that name was Kalidas, which means, “servant of the goddess Kali.” This name is very meaningful to me, as it is also the name of a great Sanskrit poet.

ESP: You have a fascinating background, especially in regards to your involvement with multiple religions. What is your overall perspective on spirituality and religious dogmas?

LC: First off, there are absolutely no dogmas in anything I practice or teach. As a matter of fact, I really am a great subversive and my belief is in destroying all religious dogmas by not following them. I’ve converted to Islam, Christianity and Hinduism, and I was born Jewish. I literally and legally converted to those religions—not so much to practice them, but for mystical reasons. It’s not so much the religions themselves, but the great teachings of those religions that I’m interested in. The only reasons for the conversions were the same as 17th century Kabbalist Sabbatai Zevi and his 18th century successor Jacob Frank, as well as Ramakrishna, who also practiced all religions to release the holiness—the “sparks of God”—that were trapped within the religious practices. So that was my intention for the multiple conversions.

If I were to practice any religion, at all—and I don’t—it would be Hinduism. I love Hinduism, and the reason is that it’s not really a religion at it’s highest plan. Now the Vedanta—which I was initiated into and practiced all of my adult life—it is a consciousness of consciousness: it is not the worship of a god or the practice of religious rituals. It actually has guided me all through my spiritual life. My poetry, by the way, is an extension of that. Because what I’m doing in my spiritual practice is to listen to the voices that are in there. And they are in there… literally—not metaphorically, not symbolically, but quite literally and are prominently, they are in there. Carl Jung talks about that. He calls them the archetypes. But the archetypes are not created by us; if anything, we are created by them. My spirituality has always to been to connect with them and to listen to them and to be guided by them spiritually.

My poetry has always been the same—when I write a poem, I’m not writing the poem, they are writing the poem. I’m literally putting myself in a place of consciousness where I can hear them and listen to them, and as accurately as possible transcribe what they are telling me, so that the poem becomes a collaboration between them and me. That’s the connection between my spirituality and my poetry. I started writing poetry long before I entered into these spiritual practices. I started writing poetry when I was ten years old.

ESP: You’ve had the “spark” all of your life?

LC: Yes, all of my life. I was a very peculiar child: as very young child, I wrote poetry and talked about God all of the time. My parents were horrified. The people around me, they didn’t understand it. They didn’t particularly like it.

ESP: People tend to shun things and ideas that are foreign to them.

LC: Oh yeah! I understand that now, but I didn’t understand that so much then. When my mother discovered I was writing poetry, it was on a bus. I told her I was writing poetry as we were going somewhere. Again, I was only ten years old. She said, “Oh my god, you must stop that! Don’t write poetry, people will call you a fagela!” “Fagel” is Yiddish for “bird,” but it also means a gay person. And I didn’t stop, but she just was horribly uncomfortable about it.

ESP: So clearly the “spark” was much stronger than the negativity that surrounded you.

LC: Oh, yes. I cannot think of any other reason why I survived this long, frankly.

ESP: When you talk about this elevated state of consciousness—where you’re able to access these divine speeches—is there a process that you go through, like mediation?

LC: Well, there has been—yes and no. I think that’s a good question. I’ve often thought about teaching meditation and creativity. The meditation that I have done—that I did—all of my life, has mostly been under the guidance of a God-realized master, in a God-realized lineage. I sat at the feet of a great master, who learned and had his experiences at the feet of another master, who learned and experienced at the feet of Ramakrishna himself. So I’m what’s called the Guru Tradition. It’s not so much an intellectual communication as a spiritual one. And the mediation and all of those practices draw me to finally what is called in Hinduism Samhadi. Samhadi is a non-cognitive experience—it’s totally non-cognitive. You’re not aware that you’re in it, and you’re only aware that you’ve been in it when you come out of it. It really changes nothing… but it does. It shifts one’s entire perception, one’s consciousness. It doesn’t make anybody any higher—I was just as big of an asshole when I came out of it as when I went in. The difference was now I truly understood that I was. And I truly understood that there is absolutely nothing—everything is bullshit. Everything is bullshit. Including what I’m talking to you now about. The only thing is, we have to choose which pile of bullshit is best to fertilize our little garden, and then we choose it. But it’s still bullshit.

ESP: That’s exactly how I feel.

LC: Wonderful, I’m really glad to hear that. So, I’m not teaching the truth—God help me if anybody were to think I’m teaching the truth, or I am trying to convey any truths in my poetry, I am not. But anyways, getting back to the question: all of that preparation and that experience and my Jungian work.

My Jungian work was much like my work with my Hindu masters: I spent six years under the apprenticeship of a man named James Kirsch, who was one of Jung’s original inner circle, and the founder of the Los Angeles Jung Institute. It was a great privilege. And working with me exactly how Jung had worked with him, I acquired the ability to listen to and hear them in there. Jung was, in effect, my grandfather. My mentor James Kirsch was his son, spiritually.Understand that they are not products of me. If anything, my consciousness is a product of them. One of the ways that Jungians really listen to them is by listening to one’s dreams and learning how to translate them under a master who has learned to do it under another master. That takes a while, because they in there speak in symbols. So it’s matter of learning how to open one’s self to those symbols and listen to them while one is dreaming, and when one comes out of the dream. After learning that over six years, James said to me, “Now you are ready to do with others what I have been doing with you.” And that’s how you know you’re ready to teach.

Some of my dreams are actually written in my sleep. One rather recent recurring dream—I was very consciously writing it in my dream, and telling myself, “Now, you must remember this when you wake up.”

ESP: So how did you remember it?

LC: I remember it in the dream. Because I have established what Jung called Auseinandersetzung—the tête-à-tête with them in there and me out here. So it was an actual conversation with them. They are actually submitting these lines of poetry to me, and I remembered it because it was a real conversation—the same way I remember what you and I said to each other.

ESP: A lot of great writers will get inspiration from their dreams—especially dreams that are extraordinarily vivid. It sounds like you’re having that sort of clarity.

LC: Yes, exactly. But it’s also the ability to realize that you’re dreaming while you’re in the dream. Some people call that “lucid dreaming” and look for it. I think that’s wrong—I think that you don’t look for making the dream happen, you look for being open to what they are telling you in there, and to remembering it vividly. So yes, that’s actually what’s going on… and it’s a question of learning how through experience and practice to have those dreams. So that’s how I learned it.

ESP: Let’s talk a little bit more about your academics: please give me a little walk through your academics and life as a whole.

I was one of the worst students in the world. I don’t know how I managed to ever get through an M.A. and a doctoral degree, but I did. But, I was extremely fortunate to have a free liberal arts education, with the humanities as a requirement—which I don’t believe that’s the case any longer. College is looked upon now as a trade school, but when I went to college, I was required to take classes in philosophy, poetry, drama, literature, art, architecture, music—wonderful classes. And before I went to college, to be perfectly honest with you, I was a product of a middle-class Jewish family: they never read a book and I never saw them reading a newspaper; I grew up in that, and yet I knew there was more. When I took those classes in college, the liberal arts classes—particularly in arts, music and literature—it was literally like my brain exploded and opened up. It was such a remarkable experience for me that I’ll never forget it—it totally altered my life. Now, I was terrible in the other classes. I never took algebra—I managed to sneak out of having to take algebra. But in those liberal arts classes, I excelled, fortunately, and they just opened my mind.

ESP: So, you studied religion and philosophy—that was your major in undergrad?

LC: Well, philosophy was my major, yes. And part of that was taking classes in comparative religion and so forth. But I have to say, even before that, I was—as a child—obsessed with God. I started reading the Bible when I was, maybe, nine years old, and I had to hide it from my parents because it was both an Old Testament and a New Testament version. And if they had seen that I was reading the New Testament there would have been Hell.

I remember from the time I was in my crib, the following kinds of things were happening: I remember—now this is not something that came up in a dream or came up under hypnosis or anything like that—it’s just I remember it as something that had happened. I would be laying in my crib in my pajamas—I was just a little kid, I had just learned to talk, I was just two or three years old. And I’d be lying on my stomach with my face in the pillow, and I would suddenly start to hear this vibrating sound in the background—which I’ve come to realize now that it’s Om. And when that would happen, I would think to myself in whatever language a child at that age thinks, “Oh no… here it comes again,” because I would get very nauseated during this experience. But I did nothing to stop it, and the sound would get louder, and I would see—with my eyes closed—way off in the distance, a dot of light. And as that sound got louder, the dot of light came closer and closer and closer to my face, until it was right up against my face looking directly at me. It didn’t have the face in a way that you would know it: it was more like the Paleolithic drawings that you see of faces; kind of images of eyes moving around, and a mouth trying to speak to me, and I did not understand what it was saying. And I had that experience virtually every night for a long time. I took it—as James took it—to mean that God was calling me. There he was… there he is. That was the beginning of my madness for God. If you notice, my poetry—if anything—is also God-mad. Really. Essentially, I’m talking about God in my poetry. Not God sitting on the throne—an old man or an old lady or any of that crap—but this indefinable consciousness that is real and there. That’s what I’ve always been obsessed with, and God started talking to me at a very early age.

I remember from the time I was in my crib, the following kinds of things were happening: I remember—now this is not something that came up in a dream or came up under hypnosis or anything like that—it’s just I remember it as something that had happened. I would be laying in my crib in my pajamas—I was just a little kid, I had just learned to talk, I was just two or three years old. And I’d be lying on my stomach with my face in the pillow, and I would suddenly start to hear this vibrating sound in the background—which I’ve come to realize now that it’s Om. And when that would happen, I would think to myself in whatever language a child at that age thinks, “Oh no… here it comes again,” because I would get very nauseated during this experience. But I did nothing to stop it, and the sound would get louder, and I would see—with my eyes closed—way off in the distance, a dot of light. And as that sound got louder, the dot of light came closer and closer and closer to my face, until it was right up against my face looking directly at me. It didn’t have the face in a way that you would know it: it was more like the Paleolithic drawings that you see of faces; kind of images of eyes moving around, and a mouth trying to speak to me, and I did not understand what it was saying. And I had that experience virtually every night for a long time. I took it—as James took it—to mean that God was calling me. There he was… there he is. That was the beginning of my madness for God. If you notice, my poetry—if anything—is also God-mad. Really. Essentially, I’m talking about God in my poetry. Not God sitting on the throne—an old man or an old lady or any of that crap—but this indefinable consciousness that is real and there. That’s what I’ve always been obsessed with, and God started talking to me at a very early age.

ESP: It sounds like an amazingly intimate experience that you had.

LC: It really was. Here was this child: I was scared, I was nauseated, but I never called out to my parents. I let it continue to happen, because that part of me knew that what was happening was significant. It just knew it.

Let me tell you another thing that happened—a lot later, but very, very similar, and relates to whom I communicate with for my poems. When I was working with James during those six years—very intensely—I had an experience. One of the things that Jung taught, and James and I had worked on, was called active imagination, where you try to get yourself “dropped down” into that state of consciousness where you’re right between waking and sleeping—you’re not awake, but you’re not asleep. That’s the place where you can hear them most profoundly. James had been teaching me about that and guiding me. And one time I left my session with James and I’m laying on the bed, and I told myself to allow myself to drift into that place, and honest to God, I heard it. Not in my head, but in the room, with my eyes closed. And it sounded like “[raspy, faint voice] Laaarry… Laaarry…” and it still terrifies me. It was so real that I jumped up, and I went to James and related the experience to him. And he says, “Well, what did you do? What did you say?” I said, “I didn’t do anything, it so frightened me that I jumped up.” James said to me, “Now look, the next time that happens—and it will happen again—you must say hineni hashem: ‘I am here, Lord.’ When the voice calls you and you hear it, you say hineni hashem.” That night or the night after that, I was doing the same thing, getting myself down into that place of active imagination, and sure enough, I hear that voice: “[raspy, faint voice] Laaarry… Laaarry…” Now, I wasn’t terrified because I had already heard this before. I said, “Hineni hashem“ just as I had been told to do. It replied, “[raspy, faint voice] What are you doing here?” Now that really scared the shit out of me: “What are you doing here?” And again, I just jumped up—it scared me. Again, I went to James, told him about it, and he said, “Well, what did you say? How did you answer?” I said, “Again, I didn’t. It really scared me.” He said, “The next time this happens—and I can assure you it’s going to happen again—what you must say when it asks “What are you doing here?” you must say, “I want to be seen by you.” I said, “Alright” and again left and went back home and again I was in that condition—active imagination—and again I heard “[raspy, faint voice] Laaarry… Laaarry…” and again I replied, “Hineni hashem—I am here Lord,” and again it said, “What are you doing here?” I then said as James had told me to say, “I want to be seen by you.” And that voice responded, “I see you, Larry.” That’s how we established the connection with them in there —to bring out the poetry that they are giving to us.

ESP: The story you just told me was essentially you unlocking the door.

LC: Yes, and allowing myself to be unlocked. If you read the Bible, it’s exactly what happens to Samuel. Samuel is sleeping, and he hears the voice calling him, “[loud and clear] Samuel! Samuel!” He then runs to his teacher the high priest, and he says, “Yes, what do you want?” And the high priest says, “I don’t want anything.” “You’re calling me.” And he said, “No, I did not call you.” So he goes back to his room, again he hears “[raspy, faint voice] Samuel! Samuel!” and goes running to his teacher again. He again says, “What do you want? Why are you calling me?” And the high priest responds, “I am not calling you. God is calling you. The next time he calls, you must respond: ‘Hineni.’” And that’s how He came to Samuel.

ESP: Let’s talk about your poetry and who you would list as your primary influences.

LC: Oh, I love talking about this. Let me start at the beginning. I was ten years old, and outside of a nursery rhyme in a book, I had never seen a poem before, let alone have the idea that they were actually written by a person. So one day in class when I was ten, there was a big cork board, and the teacher had posted on a little piece of line paper a poem one of my fellow classmates had written. I stood there reading it, and I was amazed. I had never seen such a thing before. I thought, “Wow, I can do that!” and went home and promptly started to do it—I started writing the most god-awful poetry, but I kept writing poetry from then on.

When I was around… I guess fourteen or fifteen—when I was in high school—I was in a class, I think it was a class on English. Someone passed around a piece of paper that was meant as a joke: on the left side was a passage from The Jabberwocky, and on the right side was a passage from—someone I had never heard of—T.S. Eliot‘s The Waste Land. Of course, the joke was The Waste Land made no more sense than The Jabberwocky! I got the joke, but I fell madly in love with Eliot’s poetry. And I decided at that moment, “This is the kind of poetry I want to write.” Just from that short passage from The Waste Land. I very intentionally—for years after that—I consciously and slavishly imitated Eliot, knowingly, because by doing that I was—in my mind—observing the attitude and quality of what he was doing, while my own voice was gradually emerging out it. And I think if you look at my poetry, you can see—although I’m not imitating Eliot—there’s something of that same attitude, that same worldview that you see in Eliot’s poetry without imitating him. And sometimes I get quotes from something else: popular culture, a song, or whatever, and it gets worked into the poem. Sometimes it’s lines by Eliot, and sometimes it’s a nursery rhyme, or whatever. So I was, in effect, doing what Eliot did, and have always felt that he was a major influence on me as a poet.

There are obviously other poets that I truly love: Edith Sitwell and Ezra Pound—really I love Ezra Pound—I don’t claim to understand them, but I don’t think it’s meant to be understood. E.E. Cummings—he really had a profound influence on my poetry. But mostly T.S. Eliot.

Back in the mid-1950s, when I was a student at the University of Chicago, they had at the time what they called the Committee on Social Thought, which was a collection of great international poets, philosophers, biologists, artists, and so forth, who would come and be guest lecturers for a period at the University of Chicago. Eliot was on that faculty, and in the mid-1950s, he was reading his poetry. I had the chance to go, and I did—it was awesome and just so real. It was in a small auditorium—not a big major auditorium, and it was fairly well-attended, but it wasn’t packed as now in retrospect you’d think it would be for a man like T.S. Eliot. I got a seat close up front—up close—and there he was, seated on a wooden chair, on stage left, with his knees together and his hands on his knees—just very prim and tweedy, you know? And quite vulnerable. I was very touched by it. Then he got up and he read his poetry, and—my God—I don’t remember a word of what he read, but I do remember the Q&A session afterward. One student, one listener got up and asked him, “Mr. Eliot, in one of these poems you say such and such…” and he quoted a line, and he said, “What does that mean?” And Eliot said—which I never forgot and which has guided me, if you can hear in what I’ve been saying—Eliot said, “I often write under inspiration, and I do not understand what it means when I write it. This is an example of that.” And that of course really spoke to me and my whole concept of meaninglessness in poetry.Then, after a few other people, I got up and I asked him a question. And I was shaking. I said, “Mr. Eliot, I love your poetry and it is a great inspiration for me, but I must ask you about the anti-Semitism—I’m a Jew and I must ask you about the anti-Semitism in some of your poems.” I’ve written about this, you can read it elsewhere on the internet. And Eliot responded, “When I was writing my poetry, I was the product of a social class—an upper social class—that didn’t hate Jews, but had these very condescending attitudes towards them. And that’s what was getting expressed in my poems.” He added, “However, with the coming of the Nazi atrocities, and the awareness of what had happened to the Jews by the Nazis, I and a lot of people like me realized we were not just expressing our attitudes, we were condoning violence. So I must ask you”…I swear to God he said this…“I must ask you and all of the Jewish people to forgive me for what I wrote.”

ESP: Wow, that’s really powerful. I mean, here’s someone you look up to, who has anti-Semitic roots, and he’s apologizing to you in public. I can’t even begin to fathom what that must have been like.

LC: I almost passed out, I think. [laughs]

ESP: I can imagine!

LC: But it’s so moving, I loved the man, and not just his poetry. He was a fascinating man, he was kind of a goof-off, like me entirely. He really was! He had a silly sense of humor, and I just loved him for all of that. But it truly was a remarkable experience and it really put a rounding-out to my influence by T.S. Eliot.

By the way, I learned another great poet—one of my favorites, Ezra Pound—who as you may know was also quite anti-Semitic—but he lived in Fascist Italy. I learned that, maybe, ten years ago from a colleague on the internet—a professor of English and Literature at Ohio State—that he did his doctorate on Ezra Pound, and as part of that, he got to meet with Pound and interview him. This colleague of mine is a Jew; Pound knew that. When he walked in to visit with Pound, Pound jumped up, came over to him and shook his hand, and said to him, “I want to apologize to you and all the Jewish people for the anti-Semitism I expressed.” So Pound did the same thing as Eliot. Now Pound’s wife always denied that he ever really regretted it, and put what he said to my colleague down to, “Yes he said it, but he really was just saying it.”ESP: He wasn’t earnest in what he was saying.

LC: Yes, that’s what she was saying, that he was just trying to be polite. But God, I don’t think so.

ESP: Let’s talk briefly about the prose you’ve done. Often, prose comes from a different type of inspiration than poetry, so give us an idea of where your prose comes from.

LC: My prose actually comes from the same place as the poetry does, but it gets expressed differently. The prose is mostly, really, what I can best call—though it doesn’t really describe it that well—“scholarly.” I write about the meaning of various religious works. Not the religions themselves, but the great works of revelation out of which those religions come: the Koran, the Torah, the Zohar, the Gospels, and so forth. I make very, very scholarly connections among all of them: not to show that all religions are the same—that’s ridiculous, all religions are not the same—but to show that all religious revelations, out of which these religions emerged, really come from the same source. It’s what Jung called the collective unconscious and what I try to connect with, and so forth. But I do it in a rather scholarly way, and they’ve been published in very scholarly journals and magazines.

For example, one of the things I wrote on the crucifixion of Jesus as a Jewish mystical experience was published in a journal called The Priest—a Roman Catholic journal of theology, a very highly regarded scholarly journal. And I’ve published other things in Jewish scholarly journals, and so forth. So I’m essentially touching the same place in my prose work as I am in my poetry, but I’m doing it for different reasons and with a different tone of expression. With the prose, I am seeking to have some meaning, trying to establish meaning and connections; trying to demonstrate this fundamental archetypal thing we call “God” that works its way through all religious revelations, no matter how separated they are. But in my poetry, I’m not trying to look for any meaning—on the contrary, as you might know, I don’t strive for meaning. That’s the difference between my prose work and my poetry work.

In college, I took symbolic logic, I took philosophy, and I loved them. I mean, to be honest, I excelled in symbolic logic, and I was amazed because symbolic logic is really very mathematical. It’s algebraic and I am just terrible at that, and yet I was very good at symbolic logic for some reason. So it was out of those experiences in college that my prose work began to emerge.

ESP: The prose would be the more intellectual side, and the poetry the creative side, correct?

LC: Yes, that’s correct. Both come from exactly the same place, but they get expressed differently.

ESP: If you were trapped on a desert island, and you could only have one book with you, what book would that be?

LC: The Collected Works of T.S. Eliot—in fact, I have that right next to me now! [laughs] I always have it right next to me. There’s no question in my mind.

ESP: And you didn’t even pause, you didn’t even have to think about that one.

LC: No, I don’t have to. I mean literally—and it’s not that I use it that much—but it’s always next to me.

ESP: If you could ask anybody—dead or alive—for a piece of advice, who would that be, and what would you ask them?

LC: That’s a little more difficult to answer. No doubt Carl Jung—God I wish I had been able to meet him. “Tell me what it all means,” is what I’d ask him.

ESP: Do you think he’d be able to do that for you?

LC: Oh, absolutely. Answer to Job is considered his greatest book. He once said that if he could only have one book that he’d never change a word of, he said it would be Answer to Job. That book is a book of religious revelations, like the Koran, the Old Testament, and it is the analysis of the mind of God—not the mind of man. I mean, when I first read it, I got violently ill and almost threw up, and I told James about that. And he said, “Oh, that’s not an uncommon experience.” That’s where he begins telling us out of his own direct experience with God—because he had it as I did under James—what it’s all about.

ESP: Do you have a favorite quote?

LC: Carl Jung from Answer to Job, and this is exactly what it says: “The indwelling of the Holy Spirit, the third divine person, in man, brings about a Christification of many.”

ESP: What does that mean to you?

LC: Well, it means exactly what it says. There is dormant in each of us this archetype—this literal presence which we call the Holy Spirit or the Holy Ghost. It’s a luminous, autonomous archetype, and it’s just sitting there, and it’s possible, if we can awaken it, to be exactly in the same position the man Jesus was, because that’s what happened to him. He was just an ordinary man before he went to be baptized by John the Baptist. Being baptized by John the Baptist, if you think about it, that’s when the Holy Ghost emerged from him—that awakened the Christos in him. Just as that happened to him, it can happen to all of us. You have to understand how radical that is. I mean, the Christian establishment had a fit when he wrote that because, for them, Christ happened once and for all of time, and it’s never going to happen again. And he was saying, “No, it is only just the beginning.”

ESP: That is a very powerful quote. What are your future plans and upcoming works?

ESP: That is a very powerful quote. What are your future plans and upcoming works?

LC: Well, here I am, and this coming Thursday is my 80th birthday, November 13th, and I’m giving a reading of my work that evening. My forward plans are to just keep writing—keep listening and keep writing. Interestingly, it’s often said that peoples’ productivity lessens as they get older; in my case, I’ve actually seen the reverse—my activity has absolutely increased as I’m getting older and I plan on allowing it to continue. Also, I love being an old man, and I plan on getting a whole lot older.

ESP: You’ve accumulated a great deal of knowledge over those eight decades—it has to be great being that old.

LC: Oh, I love it! Other than having to walk with a cane, I don’t look like I’m eighty, I don’t think like I’m eighty, I don’t act like I’m eighty, so I can love it without being crippled by it.

ESP: What parting advice would you give to aspiring writers out there—especially poets?

LC: Read all of the great poets—get a collection of great English and American poets—and they have such collections, they’re huge—and read them all. Read them more than you read your contemporaries. Read them and internalize them, and choose the ones that speak to you the most and try to imitate them consciously—not for the sake of ultimately being the great imitator, but to discover what it is in their work that is speaking to you, and then keep doing that until you discover your own voice, which will happen. But first and foremost, read the great poets.